Rescue Your Old Recordings

Don’t let your old tape recordings decay and become unplayable. Digital recording, specifically the sound of high-end analogue to digital converters, has now reached a quality that is totally transparent, so archival to 24-bit WAV or AIFF files is a complete ‘no-brainer’. The problem is finding a machine of the right format and, more importantly, still sounding like new to play it on. Look no further.

The studio has an extensive collection of analogue reel-to-reel machines, so we can transfer from almost all of the various mono, stereo and multi-track formats to pristine digital. More importantly, all are our machines are regularly serviced and calibrated to ensure playback quality exceeds the original specification – a labour of love for engineer Martin relying on over 40 years experience maintaining audio tape recorders. Furthermore, the azimuth angle of the play head (which adversely affects high frequencies and mono compatibility if incorrectly set) is optimally adjusted to match each and every tape or song, to match and even correct errors in alignment of the original recorder, ensuring perfect playback. Where alignment tones exist on the tape, the EQ is also adjusted to match on a tape-by-tape basis for maximum clarity, otherwise carefully calibrated standard EQ is used.

Various noise reduction formats are also on hand to match any used on your tape, again all carefully calibrated for optimum sound quality.

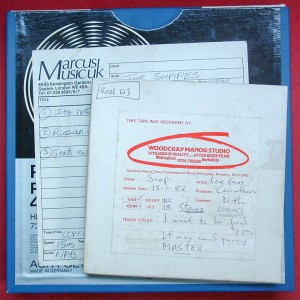

Technical details of the recording format should be written on the box (see example photo), but don’t worry if these are missing – we are used to doing the necessary detective work to get the very best quality transfer from your tape. WE WILL ONLY EVER PLAY TAPES ON THE CORRECT MACHINE, EXACTLY MATCHING THE ORIGINAL RECORDER (unlike some ‘competitors’), ensuring optimum quality. The correct playback head is absolutely critical here, hence the large collection of machines!

Digital tape masters also are not immune from degradation over time, and the playback error-correction capability has limits. This means that once enough data becomes corrupted the tape will quite suddenly become unplayable, and there is often little or no warning of such failure. Maintaining a digital ‘clone’ in WAV or AIFF format (and at least two backups of that data file, each on a different drive or storage device) is the only guarantee against this loss.

The White House was an early adopter of digital for stereo masters, firstly F1 Beta then DAT, and has always offered free archival of songs recorded and mixed in the studio. If you recorded here (or in The Basement Studio in Wokingham, 1981 to 1987) then your songs are almost certainly still available in CD quality, and modern remastering can yield spectacular improvements in the original sound. Please contact us if you’re interested, especially if you only have a cassette copy!

Tape ‘Baking’

Most professional magnetic tape manufactured after the 1970s (when new materials were introduced) develops a problem in storage known as sticky tape syndrome, a chemical breakdown of the binder (glue) that holds the essential magnetic particles in place. The problem is most severe with Ampex 406 and 456 formulations, but all which share the same chemistry are affected to some degree. Attempting to rewind or play a ‘sticky’ tape usually results in a squealing noise from the transport due to a build up of wax-like contaminants on the heads and guides, which can cause serious damage to the tape if playback is not stopped immediately. The waxy debris can stick to the playing surface, causing ‘dropouts’ – a momentary loss of signal level and clarity – and the debris must be carefully cleaned by hand. With the most severely affected tapes, the magnetic coating can also stick to the back coating, and be ripped off if spooling is attempted, causing sections of the recording to be permanently lost.

Tape ‘Baking’ Oven

Fortunately there is a cure – a precision heat treatment known as ‘baking’. This process temporarily reverses the chemical deterioration allowing perfect playback for a few weeks before the stickiness slowly returns over time.

We have invested in the safest type of unit to ‘bake’ audio tapes and cure ‘sticky tape syndrome’ – a biological incubator. The required treatment temperature is maintained within a fraction of a degree, and a sensitive fail-safe cut-out protects your irreplaceable masters in the unlikely event of a problem. The time required depends on the formulation of the tape, the state of decay and the width of the tape. ¼” stereo reels may take between 4 hours and 8 hours, while a 2” multitrack reel may need up to 20 hours. The treatment needs a slow warm-up and cool-down, and a day or so to stabilise at room temperature afterwards for best results.

It is very important to note that pre 1970s ‘pro’ formulations, and many later ‘domestic’ ones, do NOT need baking, and some can actually be damaged by heating. To ensure correct and safe handling every tape is carefully inspected and assessed before baking and playback. Please contact us for advice.

Despite the relatively long time required for successful treatment it is a very economic process, and costs are reduced by making up a batch, so please contact for a competitive quote.

Mould Contamination and Other Serious Issues

Unfortunately, mould is becoming an increasing problem with most types of magnetic tape, following long-term exposure to humid conditions. It shows as white or grey filaments or dusty powder on the tape pack, or exposed surface, which may be light or dark in colour.

For most types of analogue reel-to-reel tape this is more of an annoyance than a terminal issue, requiring extra cleaning to remove the debris. However, two Scotch formulations (206 and 256, and variants) have proved to be particularly prone, and severe contamination can result in the fungal hyphae penetrating between the magnetic coating and the backing, causing flaking at the edges and consequent dropouts. Very bad contamination may require the affected tape to be washed and carefully dried.

Mould is a particularly serious issue with domestic digital cassettes (DAT, ADAT and DTRS) as these use a very high data-density, meaning that a small patch of contamination may obscure a lot of data, resulting is glitches or even complete loss of the audio. Small amounts of debris can also clog the playback heads, requiring frequent cleaning. In a worst-case scenario, the mould can stick adjacent turns together, which can cause the delicate tape to tear when playback is attempted. The tape may possibly be re-spliced, depending on the length of the tear, but part of the recording will inevitably be lost if this happens.

Digital cassettes that were stored part-wound through (rather than fully re-wound as recommended) also have a significant area of the playing surface exposed to such contamination. ADAT tapes can be carefully cleaned on a special jig, which can improve the playback quality in such cases. Sadly, DAT and DTRS tapes are too delicate for cleaning, and the only hope is to take several playback passes, as the act of playback by the spinning head can eventually dislodge the surface debris. Error-status monitoring (see below) is essential to ensure data quality.

Scotch 206/256 and variants, and to a lesser extent some Ampex reel-to-reel examples, have also shown a tendency to bonding of the magnetic layer with the matt-back coating of the adjacent turn, probably following exposure to high temperatures over the long term. This results is complete loss of the oxide, and therefore the recording, when playback is attempted. With Ampex tapes, this is usually completely cured by the baking process. However, some of the affected Scotch tapes remain bonded after baking, and may require re-hydration for an extended period before safe playback is possible.

Finally, some early ‘acetate’ tapes have developed a chemical breakdown known as ‘vinegar decay’ because of the distinctive smell. These can usually be rescued by a re-hydration process.

Reel-to-Reel Stereo and Mono (Analogue Tape)

The most popular format for mixed masters right up until the mid 1990s. We can optimise playback and digitise stereo audio reel to reel tapes recorded with any combination of the following variables:

Track format: ½ track stereo or mono, ¼ track stereo or mono, full track mono.

Tape width: ½” and ¼”.

EQ (playback equalisation curve): NAB or IEC (AES)

Tape speed: 30ips (inches per second), 15 ips, 7.5 ips, 3.75 ips.

Spool size: up to 14″

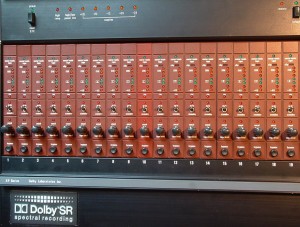

Noise reduction (if used): Dolby A, Dolby SR, Dolby B, DBX type I, DBX type II, ANT Telcom C4, BEL.

Cassettes can also be transferred as a last resort if you’ve lost the original master tape!

Reel-to-Reel Multitrack (Analogue Tape)

Tascam TSR-8 – ½” 8 track

Multitrack tapes allow remixing and reworking of older recordings using newer digital technology and results can be remarkable, especially when combined with some of the precision restoration tools now available – see the restoration page. Currently we can digitise all of the following analogue multitrack reel to reel formats (for stereo see above):

2 inch tape width: 24-track and 16-track

1 inch: 24-track, 16-track and 8-track

½ inch: 16-track, 8-track and 4-track

¼” 8-track and 4-track

EQ (playback equalisation): NAB, IEC (AES)

Speeds: 30ips, 15ips, 7.5ips and 3.75ips as appropriate for the format

Noise reduction: Dolby A, Dolby SR, Dolby S (Fostex G24S and G16S), Dolby C (Fostex E16 and G16), DBX type I, BEL, Codec (DB Electronics) as appropriate for the format

Spool size: up to 14″ for 24-track tapes, all other formats up to 10.5″

Please contact us if you have a different requirement as the collection of machines is constantly being added to. Recent additions include a customised Fostex E8, which will also play recordings made on the earlier A8, R8 and Model 80 machines, but with significantly better quality.

Fostex G24S – 1″ 24 track

Dolby Rack with ‘A-type’ cards

DAT Stereo (Digital Cassette)

Digital Audio Tape cassettes can also suffer from severe degradation over time, resulting in dropouts (clicks, glitches and gaps in the music), eventually resulting in complete failure to play. Some brands are much better than others, but all use ‘metal’ tape which has proven to be less stable than conventional ‘oxide’ formulations. Cloning of the digital data to WAV files is therefore highly desirable, allowing multiple backup copies to be maintained. This is not the same as re-recording the analogue audio output of a DAT player, which inevitably degrades sound quality by capturing the distortion and noise of the old converter chips.

We transfer DAT tapes entirely digitally. We have specially modified DAT players that log the error rates of the data from the tape during playback, meaning that problem tapes can be quickly identified. This monitoring indicates correctable errors (which do not affect the audio at all), uncorrectable errors (which the player attempts to disguise but usually result in distortion, clicks or stutters), and muting (where the player can’t make any sense of the data and switches off the audio completely). Consequently, if only ‘correctable’ errors are encountered during the transfer, the data in the WAV file will be EXACTLY what was originally recorded on the DAT – a perfect clone.

Even when the tape has started to degrade, ‘uncorrectable’ dropouts during playback are often temporary in nature, caused by dust and debris momentarily blocking the play head. Hence, even if clicks are encountered on playback, a second pass will frequently give clicks in different places and careful editing around the glitches (with single-sample precision) can also result in a perfect clone, though clearly this is somewhat time consuming and it is far better to clone the tape while still in perfect condition.

Please note that this error reporting cannot reveal glitches on a copy tape where glitches occurred during the copying. Therefore, original recording should always be used where possible for the transfer to WAV.

Certain troublesome brands of DAT may also benefit from ‘baking’ – see above.

The DAT format records at 16-bit resolution (the same as CD), but Tascam developed a unique 24-bit machine – the DA45HR – which ran at twice the usual speed, and we have now added one of these to our collection, since such tapes cannot be played on a standard machine. Still waiting for the first tape to play on it!

F1 Beta Stereo (Digital on Betamax Cassette)

We can correctly transfer Sony F1 Betamax tapes (European PAL/SECAM only, not NTSC). This was the first CD quality ‘pro-consumer’ format available, pre-dating DAT. It used an adaptor to convert audio to digital data which could be recorded on a domestic video cassette, usually Betamax because of the superior performance over VHS. Sound quality was remarkably good for the time, but some technical quirks of the system must be addressed for correct sound playback:

1 The F1 and later 501, 601 and 701 adaptors included ‘pre-emphasis/de-emphasis’ circuits to reduce noise introduced by the old-technology A-to-D and D-to-A converters. ‘De-emphasis’ of the analogue output signal is automatic because an identity ‘flag’ is embedded in the data. The F1 and 501 always recorded with emphasis ‘on’, the 701 could be ‘broadcast-modified’ to bypass the pre-emphasis.

2 At that time A-to-D and D-to-A converters were expensive and a single ‘chip’ was used to encode and decode the playback of both L and R channels, resulting is a very slight time delay (actually a half-sample) between the two channels in the digital data. Consequently summing two stereo channels to mono resulted in a slight loss of high frequencies. Audio & Design Recording produced an add-on converter to correct for this loss, but it required processing of the signal both before and after the F1 unit. These encoded tapes should be labelled ‘CTC’ (Coincident Time Correction) and need to have a suitable CTC decoder for correct playback, which we have.

CTC-encoded tapes can ONLY be correctly decoded in the analogue domain. Since recording the analogue output of the F1/501 adaptor also adds the distortion and noise of the old converter chips inside, playback through an external high-end D to A is the preferred method of transfer, which is exactly what we do.

Regular (non-CTC) tapes can now be cloned entirely digitally, and the half-sample error and emphasis corrected with digital processing. This offers superior quality, and is the preferred method of transfer, but correct identification of the ’emphasis’ is essential. Also, the modified 501/601 adaptor used reports errors in a similar way to the DAT process described above, logged alongside the audio file, highlighting any issues for investigation and best possible confidence in the data integrity.

Recordings on the F1 Betamax format have proved to be far more durable than DAT, but spares for Betamax machines are now non-existent, so transfer while a working machine is still available is essential.

Occasionally the F1-PCM family of adaptors were used with a different video recorder – VHS and Betacam have both been known, and these tapes should also be transferrable.

ADAT 8-Track (Digital on SVHS Cassette)

We can digitally transfer all ADAT format tapes to WAV or AIFF with perfect sync on multi-tape sessions. Each SVHS tape carries 8 audio tracks, with multiple machines used to record more tracks if required, so they usually come in pairs or threes, allowing 16 or 24 tracks. The early machines were 16 bit resolution and designed to run at 48kHz, but could be ‘slowed down’ using vari-speed to be compatible with 44.1kHz CDs. Later (type II) machines improved the sound with 20-bit recording and added official 44.1kHz support. The sound quality was good by the standards of the day, but not a patch on modern D-to-A converters, so transfers should always be carried out by digital ‘light-pipe’ optical connections for best results, which is what we do.

We have top-of-the-range M20 machines, which feature 20-bit resolution, the most durable mechanism and error-rate reporting, allowing playback problems to be highlighted. As with DAT, dropouts can occur randomly during playback, so two passes are usually taken to allow editing around any clicks or distortion encountered. We transfer digitally via optical links to the HD24, a later hard disc version of the ADAT which replaced the tape-based decks. Sync this way is sample accurate, allowing two or more playback passes to be perfectly aligned for editing, and WAV or AIFF files can be efficiently exported.

Alesis no longer have spares for tape-based ADAT machines and transfer is highly recommended while it is still possible.

As with DATs, certain brands of tape have shown to be very troublesome and prone to serious decay, but again ‘baking’ can help. Multiple passes are also recommended with any digital multitrack format, as glitches can be only on one track, and hard to hear with all audio tracks playing at once.

DTRS 8-Track (Digital on Hi8 Cassette)

DTRS was developed by Tascam as an alternative to the popular Alesis ADAT, but using the smaller Hi8 video tape. They made various models: DA38, DA78, DA 88, DA78HR and DA98HR. Like ADAT the machines offered 8-tracks per tape and could sync together to offer serious multitrack capability. The early machines were 16 bit resolution, but ‘HR’ models increased resolution to 24 bits and added sampling frequencies up to 192kHz (in the top-of-the-range DA98HR) by sacrificing the number of audio tracks per tape.

Many video facilities used these machines for soundtrack work thanks to the integral timecode.

We can digitally transfer all DTRS-format tapes to WAV, BWAV or AIFF with perfect sync on multi-tape sessions, via TDIF cables straight into Pro Tools, which also ensures video sync is maintained.

We have the latest Tascam DA98HR machines which feature error-rate reporting, allowing any playback problems to be highlighted – important as the data density is very high and even small amounts of dust can cause dropouts and glitches. These can occur randomly during playback even with new tapes, so two passes are usually taken to allow editing around any clicks or distortion encountered. Certain brands of tape have shown to be very troublesome and prone to serious decay, but ‘baking’ has proved to be successful in most cases.

As with ADATs, a second pass for safety is highly recommended in case glitches are discovered on individual tracks during a new mix.

Alesis HD24 24-Track (Digital on Hard Drive)

We can extract WAV or AIFF files directly from these hard discs, either installed in a ‘caddy’ or as a bare drive. Unlike ADAT tapes, these hard-disc machines recorded up to 24 tracks per machine. There were two models – one basic and one with significantly better converters and therefore sound quality. Because of the relatively low cost these were used by many studios, and also frequently for capturing ‘live’ sound directly from a large PA desk. To get 24 tracks of 24-bit audio to reliably record onto the slow hard drives of the day, the drives had a unique format dedicated to fast streaming, and which can’t be read directly by a PC or Mac. Connecting such a drive to a computer will usually prompt a ‘reformat required’ message, which, if followed, will erase your audio. We have the correct adaptor and software to allow reading the drive and safely extracting the files.

IT professionals say that there are two types of computer users – those that have lost data due to a hard-drive failing, and those that have YET to lose data… Keeping WAV file backups of HD24 data drives is your only guarantee against such failure.

4-track Cassettes

Not a professional format, but by popular request we have recently acquired and completely renovated 4-track cassette machines to transfer tapes of the most widely used ‘demo’ formats. The original Tascam ‘Portastudio’ series used DBX noise reduction and ran at twice the normal cassette speed – 3.75 ips, while later (and cheaper) machines such as those made by Fostex used 1.875 ips, and either Dolby B or C noise reduction. We can now transfer all three of these formats.

Vinyl Records

While working from the original master tape is always the best way to go, sometimes this just isn’t possible, so as a last resort we can wash vinyl discs, transfer to WAV and digitally remove the remaining clicks, rumble and as much surface noise as possible, and master for re-issue on CD, download or even back to vinyl!

This process is very time consuming: each click needs to be removed manually, to prevent the details of percussive elements in the music being destroyed, so is only suitable where no viable master tape (or safety copy) exists, and for commercial re-issue only – please don’t ask us to clean up your treasured record collection!